Tuesday, August 13, 2024

World's Greatest Super Hero Cups - Mission Accomplished

Monday, April 4, 2022

Frank Miller's DARK KNIGHT RETURNS: good or bad?

So, that's not a totally fair title, but I prefer it to my original click-bait idea: "Why do I accept Frank Millers' Fascistic Superman?" Anyway...

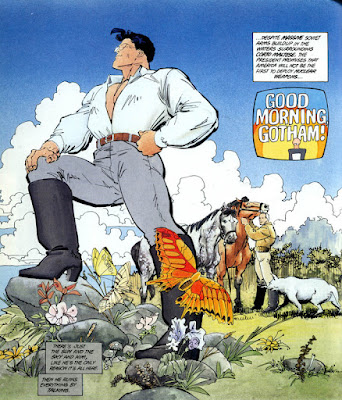

Batman: The Dark Knight Returns by Frank Miller, Klaus Janson, and Lynn Varley.

One of the best selling comics of all time.

One of the most influential comics of all time.

A classic from one of the all-time great creators in comics.

You may not read comics, but it's quite possible you have read Dark Knight. Along with Alan Moore's & Dave Gibbons's Watchmen, it ushered in a new era of superhero comics from which we have yet to disentangle ourselves, despite attempts to do just that by many creators, including Alan Moore himself. But! This is a post about Dark Knight, so let's get to it.

Since the start of COVID, my buddies and I have been talking comics over Zoom, on a weekly basis. Our latest discussion was on Dark Knight, and it didn't go as I expected. Popular opinion would have you believe this work is unassailable, a pinnacle of comic book storytelling, the greatest Batman tale ever told, a superhero story for the ages. For the most part, you would get little argument from me ('greatest' might be a stretch, but it's in the discussion). So, when a couple of my friends revealed the clay feet upon which this classic piece of comic art stands, I was surprised. But they're smart dudes, so I was ready to hear them out . . . and then tell them why they were wrong!

An aside: I feel like I should get my personal history with this book out there, because it is pertinent to the discussion as well as to my consideration of the book. I started collecting comics in 1984, when I was 12 years old. I grew up in a small town and did not discover comic book shops until 1988 or '89. In 1987, I found the Warner Books edition of Dark Knight Returns, in my local bookstore, Mr. Paperback's. I immediately bought it. Having read very few -- and possibly none at all -- Batman comics at that point, this was basically my introduction to the character. It made a lasting impression on me, and I have re-read it multiple times through the years. I know it well, and I thoroughly enjoy it.

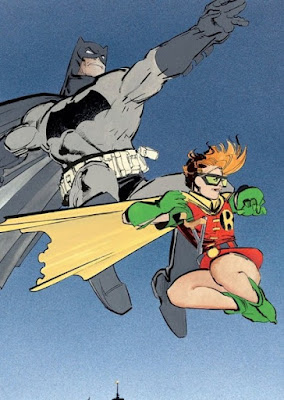

Aside #2: A brief summary of Dark Knight. Bruce Wayne is 55 years old. Batman has not been seen for a decade. Superheroes have been outlawed, and even saying their names on television is not allowed. The only one left is Superman, working covertly for the U.S. government. But, the animal inside cannot be contained, Batman returns to clean up Gotham, and Superman is sent in to stop him; it ends in a stalemate. Except . . . Bruce is good with chemicals, and he ingested a concoction that made him appear dead when he was merely in hibernation. Kal-El (Superman) attends the funeral, and his super-hearing picks up a heartbeat, just as he's about to leave. But he's willing to let Bruce wage his war, if he keeps it low-key.

Two of my friends were critical of Dark Knight, one more than the other. Their main point of contention was the characterization of the two main heroes: Batman and Superman. Both of them felt that Miller wrote these characters completely wrong. Regarding Batman, they could never see him giving up on Gotham or going into retirement; it's not in Bruce Wayne's nature. He's obsessed about instilling fear into criminals in order to clean up his city and make sure nobody ever experiences the tragedy he did when his parents were shot dead in Crime Alley. Superman, to their minds, is written as a bootlicker who follows orders from a fascist authoritarian, in the form of the broadly satirical Ronald Reagan. The prime example of this comes after the nuclear fallout of the missile Superman barely diverted. Even with crime rampant in cities across America, Gotham -- previously the most dangerous city in America -- is now experiencing a substantial decrease in crime due to the Batman's actions. Despite that, Superman is sent into Gotham to put a stop to Batman. Because, the law.

These points are valid. In all honesty, I'd never thought too deeply about the characterizations of Batman and Superman, or the other supporting characters, in this book. I just went along for the ride. That said, I agree completely that Batman and Superman are totally out of character in Dark Knight. But, I don't think that's a problem. And here's why: because I love being right!

Or maybe there are better reasons.

The most important thing to remember -- despite DC's desire to shoehorn this book into Batman's main continuity -- is that Batman: the Dark Knight Returns is an Elseworlds story, a tale from a parallel universe, where all the heroes' names are the same, but they are, to various degrees, slightly different. This is essential, I feel, to accepting and fully understanding Dark Knight.

(Allowing that all art is subjective, so you may understand it differently, and that's cool too, but wishy-washy statements don't make for compelling arguments. But I digress. Let's get back to our regularly scheduled program.)

In this Dark Knight continuity, Batman and Superman (as well as all the other notable characters) have aged beyond the perpetual 28 years they inhabit in the main comic books. Bruce Wayne is roughly 55, as Miller wished to make the character as old as his legend. Superman would also be around 55, though his Kryptonian physiology seems not to have dampened his powers. Jumping off from there, Miller wanted to craft a narrative that examined what a Bruce Wayne/Batman of 55 might be like. He wanted to look at how that would have affected him not only physically, but also emotionally. Sure, Bruce Wayne is a superhero, but age has a way of slowing you down, making you second guess your abilities, infusing doubt where it might not have resided before. It's an intriguing premise, and one that I appreciate seeing played out in Dark Knight.

These characters have also experienced very real change in their lives, and they live with that hanging over them. Again, this is unlike the main comics in that, though there is the illusion of change and the hyperbole of earth-shattering events in those books, for the most part these incidents have very little impact on the characters. DC, as a publishing entity, needs to keep the status very much in quo so people will continue to buy their comics. There can be no real changes in these characters' lives; it's too much of a risk. Therefore, Batman, Superman, et al. plod along, ageless icons, experiencing titanic events, but never seeming to feel their repercussions.

Miller wasn't interested in working within the status quo. He wanted to put these heroes under a microscope and poke at them, see how they might react to having experienced real tragedy, real change, real evolution. Jason Todd died ten years prior, a cataclysmic event from which Bruce Wayne found it nearly impossible to come back. For a decade he allowed Batman to remain dormant, so that no such personal tragedy might happen again. It can be assumed that, even if he were not directly responsible (and maybe he was), Bruce feels wholly responsible for the death of Jason, who took the mantle of Robin after Dick Grayson grew out of the name. This has weighed heavily upon him.

Also in that time, superheroes have been outlawed. It seems a safe assumption that the timeline for this legislation parallels that of Bruce's tragedy -- ten years. As a result, Hal Jordan (Green Lantern) left Earth for the stars, Diana Prince (Wonder Woman) went back to her people, and Superman became the not-so-secret secret weapon of the U.S. government. Similar to the disbanding of the Justice Society when they refused to divulge their identities in the HUAC hearings, it can be assumed that heroes became suspect by regular civilians, that they were no longer trusted, and, thus, outlawed. Most of them retired, but Superman could not. His powers, and the responsibility instilled in him by Ma & Pa Kent -- who also taught him to respect authority, an important point -- meant he needed to find a way to continue helping humanity. So, he took the only path that he felt had been afforded him. He worked under guidance from the U.S. government, keeping a low profile but still doing good.

Both of these heroes have gone through personal upheaval and been changed by that. This is why, I think, I am able to accept their characterizations, even if they are "off" from how they are regularly written. Superman has always been the rule follower, while Batman the rule breaker, and the idea that Superman would go along with the government if it meant he could contribute to bettering the world, even in some small way, works for me. Batman was responsible -- at least indirectly -- for the death of a teenager, Jason Todd. This would have a profound effect on Bruce Wayne, could cause him to turn in on himself and reevaluate his actions. Extrapolating from that, he might retire, give up on Gotham, and try to just live out the rest of his life in a way that wouldn't put another child in danger.

Of course, in the end, Bruce Wayne returns to Batman. And, in my reading of those final pages, Superman, with a knowing wink to Carrie Kelly, the new Robin, learns that there may be another way to help this adoptive world of his.

Ultimately, these characterizations were due to Frank Miller wanting a battle between Batman and Superman at the end of Dark Knight. He needed them to be on opposite sides of the fence, so that he could bring them to Crime Alley, along with Oliver Queen, and show readers that given enough money, ingenuity, and obstinacy, a human can defeat a superhuman in battle, even if that victory is fleeting.

Monday, September 13, 2021

Time in Comics -- it works differently

In fiction, time works differently than in real life. It has to, because very often the stories we read or watch or listen to take place over the course of many days, months, or years, while we experience them in a matter of hours or days. (Alan Moore's JERUSALEM took me months, but that's a whole different beast, that.) In no other medium, though, is the idea of time more malleable or more fluid than in comic books. It's part of what I love about them.

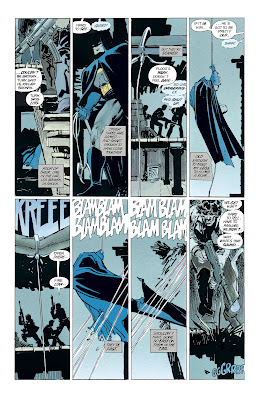

As a story distribution vehicle, the comic book, in its most recognizable form -- roughly 20 pages of words and images combined to relate the most recent narrative chapter of a particular, brightly garbed hero's adventures on a monthly basis -- is, perhaps, the most compressed story distribution vehicle, as regards the geographical space with which writers and artists have to work. The page count has fluctuated over the past few decades, from 17 pages with a shorter backup feature in many late-70s DC comics, to 24 pages through the 80s and 90s, to around 20 pages today. An average page may have 6 panels on it, each a snapshot of a specific moment in time, but there are also splash pages -- a single image encompassing the entirety of a page to convey a moment of high drama or cool action. And although some artists may layout pages with more than 6 panels (George Pérez could do wonders in the tiny spaces necessitated by ten or twelve or fifteen panels to a page), many will often utilize fewer panels per page to tell their story. So, creators have somewhere fewer than 120 images -- and more likely fewer than 100 or 90, to be honest -- to get across what they want to say for that month, in that chapter. It's not a lot of room.

With those limitations of space, comic creators had to figure out ways to infuse the most narrative punch in as economical a way as possible. Early in comics' history, that meant a whole lot of word balloons and thought bubbles stuffed with text that, in my opinion, dragged the narrative to a screeching halt, leaving it as limp as a pile of wet leaves. Blechh. These writers and artists, though, also figured out some tricks hidden within the mechanics of the comic page. A prime example would be the gutters, the empty spaces in between the panels. Depending on the transition between images from one panel to the next, a lot or a little could occur in the gutter. If the artist merely drew a succession of images that linked together like those flip books we used to have, then the reader had little to do in order to get what was going on. Nothing's in the gutters; it's all on the page. But, if the creators jumped from one image in one scene to a totally different image from another scene (probably set in the near future, possibly set in the past, maybe even running parallel . . . take your pick!), a connection could be made, subconsciously, between these two images. And maybe, as more context became evident as one continued reading, there would be a direct correlation between these seemingly disparate scenes. Perhaps some action in that first scene spurred what occurred in the following scene, even if it took place in a different locale at a different point in time.

When this happens, the gutter becomes paramount in the narrative flow, because whatever happened in between these two images, which may sit side-by-side or possibly connect through a page-turn, happened within that empty space separating them, and now the reader gets to fill that in with their imagination. The gutter is the magic spark within comic books, and it makes the reader a participant within the narrative, allowing for the tapestry of a comic to expand to a (theoretically) limitless tableau.

The publication schedule of comics -- for the most part series have run on a monthly basis, though it's common today for more popular series to run every two weeks -- is another aspect that injects time into a comic narrative. With a month between issues, readers have all that time to ponder the most recent chapter of a hero's story, to mull it over, consider the ramifications, hypothesize about what may come next or how the hero could possibly escape that issue's cliffhanger. In short, this 4-week hiatus between issues allows the story to build in the audience's mind while also expanding time within the narrative itself. From one issue to the next, as much time as a week or a month could pass, or as little as a minute. But in our brains, even if very little time passes in Batman's story from issue #546 to #547 (as a hypothetical example), readers have still experienced a month, and that added time can help with the storytelling, because things that may have happened "too quickly" in the previous issue now have the benefit of a whole month passing, tempering the coincidental nature of some of the previous actions.

Which all sounds far too abstract. Let me try to illuminate this argument with a concrete example:

In the wake of DC's mega-event, Crisis on Infinite Earths, time was reset and the history of the DC universe was re-arranged and streamlined. The comics published by DC afterward needed to reflect this change in status quo, and one of those titles was Batman: the New Adventures, retitled with issue #408, written by Max Allan Collins, with pencils by Chris Warner and Inks by Mike DeCarlo. In this issue -- following directly after Miller & Mazzucchelli's classic, Year One -- Batman decides to work solo again, with no Robin, after Dick Grayson is almost killed by the Joker (a phantom image of Dick as Nightwing reveals his future . . . which, playing along with the theme of this piece, has already occurred a few years in the past, as far as publication dates). As a solo crimefighter, Batman eventually meets Jason Todd, a young vagrant who stole two of the tires from the Batmobile while it was parked in Crime Alley. Impressed, Batman takes Jason to a local orphanage, promising to check up on him.

In the following issue, written again by Collins but drawn by Ross Andru & Dick Giordano, Batman discovers, through checking up on Jason, that the orphanage where he took the boy, Ma Gunn's Orphanage, is actually a headquarters for a juvenile gang run by the matriarch of the place. Thanks to Jason, Batman discovers their plan to steal a priceless diamond necklace and thwarts the pack of hoodlums and their elderly crime boss. In the end, Batman commends Jason for his work, calling him Robin, and resetting the cycle of the Dynamic Duo once more, a mere couple of dozen pages after his declaration to work alone.

Reading these two issues today, that shift from working alone to again taking on a partner -- a child partner in Batman's war on crime -- may seem abrupt on the part of the Batman. That's because it is. But reading it back in 1987, as it was being published, there would have been a month in between those issues. Readers would have had almost thirty days to digest the reality that Batman was again fighting crime solo. If one considers that during the 80s the primary audience for comic books, specifically superhero comics, was children, those thirty days are a not insignificant amount of time. So, when the Batman does a one-eighty in the very next issue, they would not have been reading it as if it was only yesterday he'd declared his return to solo vigilantism (and, in fact, there's a bit of a montage aspect in that previous issue when the creators show Batman fighting crime on his own again, indicating a relatively lengthy amount of time). To them the time that had passed in between reading these two issues could have translated to the narrative within the comic itself, allowing for a less abrupt transition back to having a Robin at Batman's side. And it seems possible that comic book creators may have taken this passage of real time into account when crafting the monthly adventures of one's favorite superhero. It's certainly a trick that would allow writers and artists to compress events in order to move the narrative along more swiftly, while also hopefully avoiding complaints of coincidence or a straining of credibility (he wears a batsuit and swings through skyscrapers on his batrope when he isn't using his batwing or batplane . . . straining credulity?!!?).

It's interesting to consider that older comics should not be read in quick succession. Many issues, even up to the 80s when I began collecting comic books, were crafted as single packets of entertainment to be digested on their own, with little, if any, connective tissue to the previous issues or those that followed (outside of the power sets of heroes and villains and characterizations of the main and supporting casts). Jim Shooter, editor-in-chief of Marvel Comics from 1978 to 1987, famously (apocryphally???) stated that creators needed to craft each issue as if it were the very first issue of a new reader. Which is a fair enough assumption. But I think adherence to such a rule wasn't necessary and could be detrimental to a creative team. My first Marvel Universe comic (as opposed to G.I. Joe or Star Wars) was Marvel Super Hero Secret Wars #4. Number Four!!!! The series was already a quarter of the way through it's twelve-issue run, starring dozens of heroes and villains with whom I had a limited experience, and I just dove in and read it. And I was hooked.

But I digress. Apologies for the tangent. Where was I? ... time in comics works differently ...

There's also the idea of characters' ages in comics. Again, specifically superhero comics. When the first original superheroes were created for comic books, the medium was seen as a cheap, throwaway bit of entertainment. Poorly reproduced art on the cheapest newsprint -- all in color for a dime! -- with little to no continuity, because who was going to hang onto these comics? Kids folded them up and stuck them in their back pockets. Issues were traded and shuffled between friends with little thought to which one belonged to which kid, because they only wanted to be able to read more and more of these adventures. And if that meant gathering with the neighborhood kids, throwing this week's issues all into a pile, and pulling out one you hadn't read yet, then so be it. With this disposability also came a lack of forethought as to the longevity of these characters. I don't believe anyone involved with the publishing of those earliest comic books expected the medium to last as long as it has. So the idea of these heroes -- Captain Marvel, Wonder Woman, Hawkman, the Flash -- aging wasn't even a consideration.

Sure, this too might strain credulity (Batman's still only 29, even though he fought against villains in 1939!), but what else would we fans of the medium want? Sure, the older Bruce Wayne in Batman Beyond is pretty damn cool, but allowing the original heroes to give up the ghost isn't something fans seem inclined to want. I mean, Barry Allen (the original, Silver Age Flash) sacrificed himself in Crisis on Infinite Earths and remained dead for a very long time, almost three decades. And Wally West ably took up the mantle, becoming, in many fans' opinions, a far better character than Barry ever was. But, even Barry was brought back, and is now, today, the primary Flash. It's too bad, because he did mean more as a character, in death, than he ever did in life. But, what're you gonna do? Time in comics doesn't work the same, and the hardest thing to do in these four-color worlds is kill off a character and have them remain dead.

-chris

Friday, April 23, 2021

Batman: Year One -- Gordon & Essen

With the continued discussion of the post-Crisis DC Universe I'm having with three of my friends, we followed up Byrne's Man of Steel with Batman: Year One by Miller & Mazzucchelli. I want to look at one, very specific aspect of this series--the relationship between Detective James Gordon and Detective Sarah Essen.

Miller & Mazzucchelli bring all their creative knowledge to the task of telling Batman's origin story, within the space of only four issues, none of them oversized. To achieve what they want, they heavily layer their storytelling, crafting full, intense scenes that take place over the course of just a couple of pages, or just a handful of panels. There's no fat on these bones, and that is true for one of the major character bits for James Gordon.

Gordon is new to Gotham, trying to be a good cop in a corrupt agency, pressured by his superiors and his fellow officers, while dealing with the anxiety that comes from the impending birth of his first child, all in a cesspool of a city. He finds solace in the arms and lips of a fellow detective, Sarah Essen.

Their blossoming relationship occurs over the course of only three scenes where they interact directly with one another. A grand total of maybe five pages, though there are another handful surrounding the personal interactions between the two. It's brief, very brief, and yet, it feels genuine, and it works. Miller & Mazzucchelli manage to infuse these scenes with the weight and the emotion and the humanity that allows us to believe that James Gordon could fall in love with this fellow detective, and that she could do the same, even with the reality of his marriage and his wife's pregnancy. It's masterful. And then, when we land on this page at the end of chapter 3, the devastating reality and the heavy guilt that Gordon is carrying with him just hits us in the gut.

Miller & Mazzucchelli have a relatively small bibliography, within the mainstream, superhero comics medium. But, in the two stories they created together, this and Daredevil: Born Again, they may have crafted the best superhero stories the medium has ever seen.

--chris

Wednesday, October 21, 2015

OCTOBER COMICS (2015): Batman & Dracula: Red Rain

Saga of the Swamp Thing #23 -- general thoughts

A brief (re)introduction. Two friends of mine, Brad & Lisa Gullickson, hosts of the Comic Book Couples Counseling podcast, are doing a...

-

A quick (re)introduction. In 1987, I walked into my local bookstore and found a collection of comics -- "Saga of the Swamp Thing...

-

Saga of the Swamp Thing #21: "The Anatomy Lesson" This is the big one! The book that changed it all -- for Swampy in particular...

-

Saga of the Swamp Thing #21: "The Anatomy Lesson" This is the comic where most readers began their appreciation of Alan Moore...