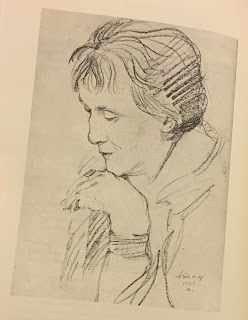

Anna Akhmatova was the preeminent Russian poet of the first half of the 20th century. It's likely you've not heard of her. Between 1912 and 1921 she had five collections of poetry published, to critical acclaim. But when her first husband, Nikolai Gumilyov, was killed for wrongly being accused as a counterrevolutionary, Akhmatova and her son Lev were also implicated. By 1924, critics panned her verse as simplistic and anachronistic, and a party resolution by the Soviet government essentially banned her from being published, though she continued to write poetry. Stalin intervened in 1939, allowing for a new publication of verse, but by 1946 another resolution censored and censured Akhmatova, leaving many of her most realized works, such as "Requiem" and "Poem Without a Hero," unpublished. But she still wrote and would share her work with confidantes, who would memorize poems and circulate them orally, so they would not be lost. Shortlisted for the Nobel Prize in 1965, not until 1988 was the resolution banning her poetry in Russia rescinded, allowing for a new and better understanding of this important 20th-century poet.

I am currently reading a "My Half Century," a curated collection of Akhmatova's prose, much of it taken from her diaries and letters. It's a fascinating book, and I wanted to share some quotes from it, through a series of posts here.

Remember Rousseau, who said: "I only lie when I cannot remember."

These both stood out for me because they speak to the heart of what it means to be a writer, particularly a fiction writer (and poetry would certainly fall under this, as well). The first is about the primary job of a fiction writer --- lying. Fiction authors lie for fame and money -- or, at the very least, to be heard by an audience of one -- but it is also about trying to get at the truth, a great truth than just the facets of a narrative. Great, and even good, fiction must be about something. And very often the fictions crafted by writers come from something in their past, whether directly transposed to the page or morphed into something more dramatic (or possibly less close to reality), and I believe that when they cannot remember, they lie.

Sometimes I unconsciously recall somebody else's phrasing and transform it into a line of poetry.

The second quote makes me think of an anecdote from Harlan Ellison, whom you may have heard of if you've read a few of my posts here on the site. One of his best-known stories, and one of my personal favorites, is titled "Jeffty is Five." It's a tragedy about a young boy who remains five years old, even while his boyhood friends grow up and start to have lives of their own. But, not only does Jeffy remain five, but he is also still able to access that olden time from when he and his friends were five, a time when radio dramas curled your blood and secret decoder rings were ubiquitous, when comics were a nickel and real chocolate was used in candy bars. It's a poignant, affecting, amazing story, and I would recommend you seek it out.

But I digress: the inspiration for this story came when Ellison was at a friend's home for a get-together. It was Walter Koenig's home, and while in conversation, Ellison overheard a snippet of another conversation wherein they were discussing a boy named Jeffery, who was five, if I'm remembering this correctly. Ellison misheard it as "Jeffty is Five," and his brain immediately started building that story, right there, in the middle of the party. In the end, it allowed him to craft one of his best stories, and it all came from something similar to the unconscious use of another's phrasing and transforming it into a bit of poetry.